Securing National-Level Support (for 911)

Effective, equitable emergency response locally requires unequivocal support federally.

What are we calling for? We are calling for federal, executive branch leadership to embrace and advance the transformative changes outlined in these recommendations. Specifically, we are calling for the president to create a time-limited 911 center and directorship by December 31, 2022, along with a federal interagency taskforce—to also include the relevant federal agencies, as well as local 911 and other related field leaders—and a National Academy of Sciences (NAS) panel. The emphasis on time limitation is made because a permanent federal home for this center should be carefully examined and ultimately recommended by the NAS panel to establish where it can best be located to serve the needs of callers and the workforce; to coordinate complex processes among the many federal, state, and local partners; bolster federal support; and weather political leadership changes. There are many considerations for 911’s long-term success that will need to be carefully considered before this center should be established.

While we strongly believe that federal leadership and guidance are critical for the transformation of 911, we emphasize that we are not calling for the federalization of the 911 emergency response system. Provision of services and authority to deploy them so should remain at the local, regional, or state level. We are calling for federal guidance and resources to support local leadership, to promote more direct connections to the community (see chapter four on the people), and to make a significant financial investment in this long-overlooked aspect of the emergency response system.

Why is this essential? Our nation’s 911 system currently functions through a patchwork of thousands of locally operated ECCs, with oversight and support split across many different federal, state, and local agencies. Local control and relevance are essential (see chapter six on independent and equal 911). But without national minimum standards to align operational procedures and ensure communication and coordination among jurisdictions, the possibility of transformation on a national scale is reduced. For example, depending on the jurisdiction, 911 emergency calls may be handled by staff who are highly trained in a variety of emergency responses or by staff who have not even been trained to help a caller administer cardiopulmonary resuscitation or who lacks access to certified language translation services. This inequity in system responses almost universally disadvantages those in small, poor, or otherwise marginalized communities, and it undermines public safety and public health.

The federal government is uniquely suited to convene stakeholders to build constituency, tap expertise, and set minimum standards for training, data, and technology. Without federal involvement, standards are not only optional; they are largely unfunded. Federal incentives, coordination, adherence monitoring, and resourcing has the power to galvanize the adoption of innovative practices and technology across geographical and operational lines—from our most rural communities to the densest urban centers.

We strongly support local control over ECCs and the 911 ecosystem. Local policymakers, ECC leadership, and 911 professionals are best positioned to know and be responsive to the local context and preferences. However, federal support and leadership can nonetheless be transformative for local systems.

This is true whether or not federal resources constitute the majority of the system’s expenditures. Consider, for example, the federal role in social welfare versus education systems. With respect to social welfare spending, the federal government outspends state and local governments by nearly double. In contrast, federal spending on education accounts for only approximately 8 percent of total education spending. Nonetheless, in both social welfare and education, federal leadership is crucial.

We emphasize that we are not calling for the federalization of 911. Rather, we are calling for the executive branch of the federal government to help advance the recommendations contained in this blueprint.

A federally created, time-limited 911 directorship, 911 center, and interagency taskforce is necessary to:

- establish the permanent consolidated placement of 911 within the federal governance ecosystem by December 31, 2024;

- help streamline local 911 operations; evaluate and implement standards, best and promising practices, and emerging technologies (see chapter eight on data and tech);

- ensure coordination, consistency, and interoperability—as appropriate—between 911 and crisis and non-emergency hotlines;

- implement a national 911 data collection effort;

- offer accountability and establish a baseline of care for callers and professionals, regardless of location in the country;

- increase coordination among emergency communications centers and encourage shared infrastructure and/or consolidation, wherever feasible;

- secure revenue, including preventing states from reappropriating 911 fees collected to other purposes; and

- incentivize continuous improvement and evolution.

Importantly, these time-limited federal structures are meant to start moving the needle on transformative change to our nation’s 911 system relatively quickly. They are designed to be time-limited so that they can eventually hand off responsibility for 911 coordination to the NAS panel, which will, in turn, consider a more permanent home for 911 on a longer-term basis.

Current challenges include a lack of common minimum standards for (1) workforce training and support, (2) data collection and reporting, and (3) technology interoperability. This means that while the emergency number people call is constant, the response’s appropriateness is highly variable. The federal government is uniquely positioned to address these challenges by setting minimum standards while incentivizing application of these standards and galvanizing durable change across geographical and operational lines. Federal funding and leadership can help shepherd local efforts so that variance between local ECCs is minimized.

Emergency services governance takes place at all levels of government—federal, state, county, and city—and these roles sometimes overlap based on geography and type of emergency service or issue. Partnerships across all levels of government and discipline are required, as is a high degree of planning and sufficient dedication of resources.

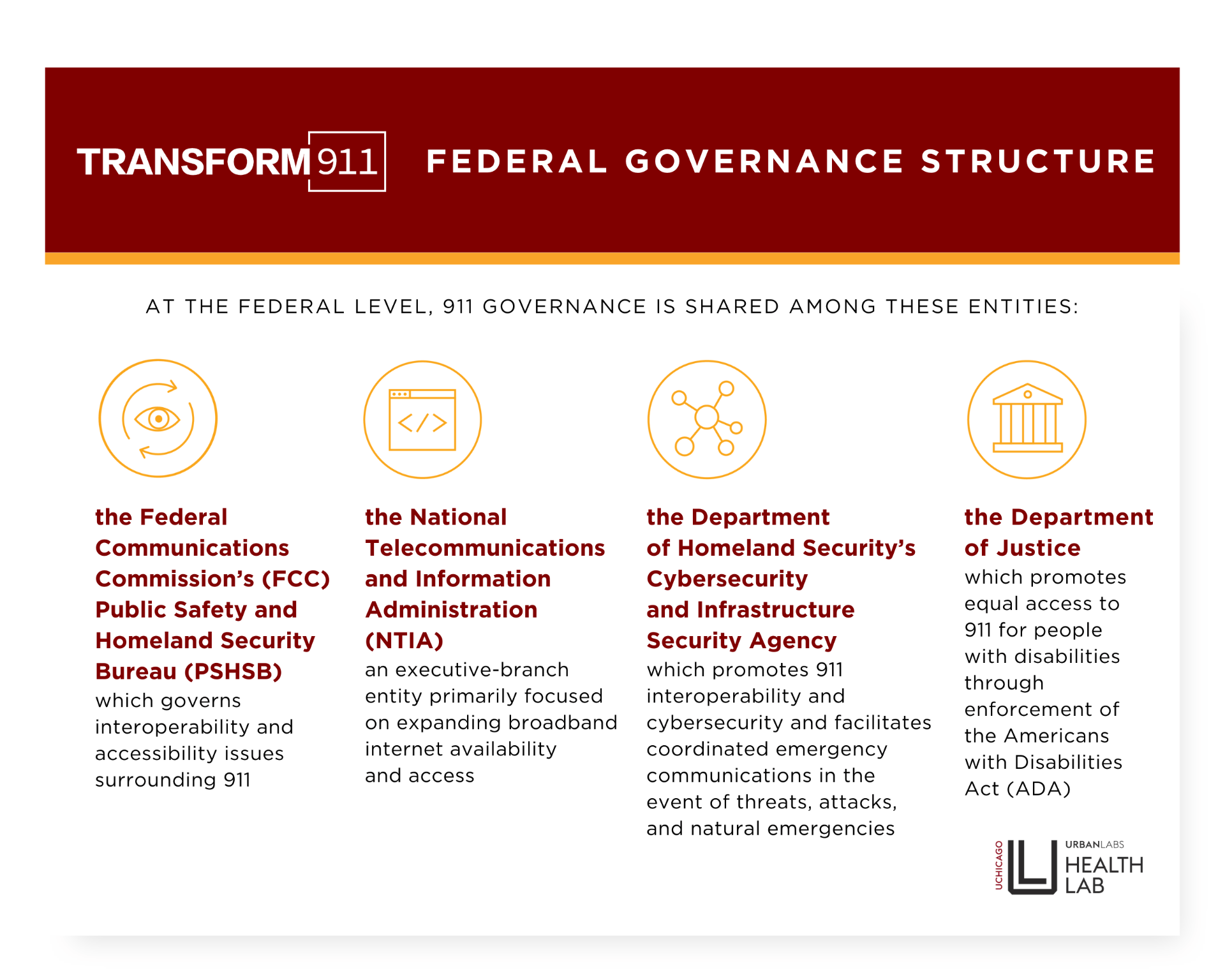

At the federal level, 911 governance is shared among the following entities:

- the Federal Communications Commission’s Public Safety and Homeland Security Bureau, which governs interoperability and accessibility issues surrounding 911;

- the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA), an executive-branch entity primarily focused on expanding broadband internet availability and access;

- the Department of Homeland Security’ Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, which promotes 911 interoperability and cybersecurity and facilitates coordinated emergency communications in the event of threats, attacks, and natural emergencies; and

- the Department of Justice, which promotes equal access to 911 for people with disabilities through enforcement of the Americans with Disabilities Act.

In addition, the National 911 Program was established to provide federal leadership to coordinate among these federal agencies along with state and local 911 services. And in 2004, passage of the ENHANCE 911 Act prescribed the establishment of a national 911 Implementation Coordination Office (ICO). The ICO is charged with coordinating between the NTIA in the US Department of Commerce and the US Department of Transportation’s National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) on 911 issues.

In short, 911 governance is diffuse and confusing even among experts, and the action items in this chapter are designed in part to provide clarity and direction.

Funding at the federal level for investments in state and tribal 911 programs occurs primarily through the National 911 Program, which at the time of this writing is housed at the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) in the US Department of Transportation (DOT). Originally authorized in 2004 for a period of five years, the National 911 Program has been reauthorized multiple times but, without further action, is currently slated to sunset on October 1, 2022. Over the past 18 years, the program has focused on a wide variety of 911-related topics, including technological upgrades (e.g., NG911 and FirstNet), 911 cybersecurity, 911-related data, legislation, workforce training, and funding issues. However, even with this federal program, gaps exist in knowledge, coordination, commitment, and support for the nation’s 911 system that must be addressed.

In addition to NHTSA/DOT, other federal departments and agencies like the Department of Justice and specifically its Bureau of Justice Assistance and the Department of Homeland Security’s State Homeland Security Grant Program also provide grants for emergency communications, which may include allocations for 911 programming. While these grants offer flexibility to state and tribal governments to address their specific 911 programming priorities, annual awards are reported based on the total amount received for all preparedness and response needs.

Upon completing an exhaustive search on funding data and considering assessments from subject matter experts in emergency preparedness, we have concluded that sufficient data do not currently exist to reliably measure the impact of federal expenditures for state, tribal, and local 911 initiatives, including support of NG911 infrastructure. This recommendation directly seeks to remediate this challenge, among other priorities.

A comprehensive assessment of federal investments in 911 and related infrastructure is essential to assess the multiple current and historical efforts. In 2019, for example, federal allocations for activities and enhancements to existing 911 programs exceeded $100 million. However, while allocations likely have been awarded in previous years, these data are not readily available. Moreover, in another example, in 2015, the US Department of Homeland Security, Science and Technology Directorate, entered into an agreement with a group of organizations led by a public-safety-focused nonprofit organization in the amount of $1,289,950 to study text-to-911 translation, in order to address the burgeoning need to ensure that people requesting emergency assistance who are not primary English speakers can smoothly access critical response.

Actions

1. Establish a short-term high-level federal executive branch leadership position and cabinet-level interagency taskforce to drive nationwide 911 transformation.

- By December 31, 2022, launch a cabinet-level interagency federal taskforce—analogous to the Federal Interagency Reentry Council—that can align funding (including making the case for the increased funding outlined below and linking it to meeting standards), messaging, public outreach, hiring practices/restrictions, and the technology taskforce recommendations outlined in Recommendation 6, chapter eight, and launch data collection efforts for the 911 system, as well as provide coordination support between 911 initiatives and other emergency response efforts such as 988 rollout.

- Have membership from senior officials within every federal agency reflected in 911 and 988 operations at the time of this writing, as well as local 911 and other related field leaders.

- Create a non-confirmed, high-level federal position, such as a national 911 director or similar position, to lead this interagency taskforce.

2. Charge the taskforce with addressing issues related to the workforce pipeline challenges described in Recommendation 3.

- See Recommendation 3, chapter five of this blueprint.

- Review hiring exclusions by June 30, 2023, and issue a federal fact sheet detailing mandatory and optional disqualifying criteria.

3. Develop baseline minimum credentialing and training standards. Charge the taskforce with instilling a process that will ensure immediate and continuous data collection and learning. By June 30, 2023, the taskforce should establish a process to consolidate and issue its first report on 911 to provide basic statistics.

- Several organizations have taken steps to enumerate recommended minimum training standards and training topics for 911 professionals, including APCO, NENA, the Denise Amber Lee Foundation, and others. We are not recommending any particular set of existing standards; rather, we are recommending that the taskforce appoint experts to determine the requisite standards.

- Address the reality that comprehensive data on 911 is currently lacking, due to the fact that there is no publicly available national data collection pertaining to 911.[1] Because one of the most important things the federal government must do immediately is enable a basic understanding of the 911 system through access to available data:

- Inventory the currently federally collected data relevant to 911.

- Recommend new data collection requirements and performance standards.

- Create a national scorecard system to encourage learning across jurisdictions that will serve as the basis for an expanded version, as determined by the NAS panel (described below).

- Coordinate immediately with the Federal Communications Commission to obtain, organize, and consolidate data with and from the national telecom vendors to produce and document the data they currently have available.

- Immediately collect available data from ECCs, considering what is easily accessible as well as what additional information could be gathered from the Federal Communications Commission’s master Public Safety Answering Point (PSAP), or ECC, registry and related data collection efforts. Also consider opportunities to expand this data collection, its costs, and any limitations. In particular, it is important to understand ECC governance structures, personnel size, call volume, response options, resource allocations, and training and hiring requirements, among other factors that define each ECC.

- Update and continue to maintain the GeoPlatform ArcGIS PSAP 911 Service Area Boundaries map. This map is a helpful tool, but it sits outside the federal government’s infrastructure and does not appear to be regularly updated. This resource should be maintained regularly, federally, and updated at least annually. It should also be in an environment where users with a variety of skills and interests can easily add and remove other elements (e.g., city/county/census tract boundaries and related statistics).

4. Institute the 911 data and technology ethics component of the federal taskforce and oversee its charge, including the creation of guidelines for data capture, ownership, sharing, and analysis.

- See chapter eight on data and tech.

- Appoint cross-sector, multilevel stakeholders including impacted communities, state and local policymakers, 911 administrators and telecommunicators, technology vendors, technologists, first responders, and behavioral health specialists.

- Concretize the taskforce’s charge in regard to the scope of the work to develop clear, plain-language explanations on the use of emergency response data including a description and purpose of any software algorithms, the data used, mechanisms for human oversight, and any risk-mitigation techniques.

5. Ensure equitable funding for ongoing 911 operations.

- Reduce or eliminate the practice of states’ reappropriating 911 revenues to fund other unrelated activities (which leaves ECCs under-resourced and unable to provide the care that communities need and expect). Instead, tie federal 911 funding to compliance.

- To ensure adequate and equitable funding, the taskforce should evaluate the prevalence of this issue[2] and recommend tactics to cease its practice, whether that be in the form of an executive order, agency directive, or act of Congress.

- Consolidate existing funding streams to create a formula grant program to states and localities for annual operating support.

- Increase the affordability and effectiveness of 911 for the people who pay for it.

- With the vast majority of 911 communications increasingly coming from mobile devices, fees being generated by billing location are likely not the same place as where 911 calls (or associated ECC) are initiated. For a variety of reasons, the 911 service consumers pay for is likely not the 911 service a caller has access to when reaching out to 911.

6. Establish and launch a NAS panel by December 31, 2022, to consider and provide final recommendations by March 31, 2024. Since it is expected that the NAS panel will take time to inaugurate, the short-term federal interagency taskforce is designed to commence more swiftly, after which the panel will step in regarding the establishment of the following:

- The final and permanent placement of 911 within the federal government.

- Ensure permanent home for a 911 center that conducts regular review and updates of workforce training, credentialing, and staffing standards.

- Determine the time frame and review template for this work.

- A set of national consistent standards, including baselines for:

- Establishing national and state-level minimum standards for how ECCs operate to ensure consistent, equitable access and delivery of 911 services and related certified response options (e.g., certified language translation and standards for training in cardiopulmonary resuscitation), regardless of location in the country.

- These standards should be crafted in such a way as to provide for the differences between operating systems in different contexts (e.g., urban versus rural locations).

- Standards should include call-taking and dispatching procedures, protocols, practices, data collection, and key performance indicators.

- They should be developed in close collaboration with industry leaders such as the Association of Public-Safety Communications Officials (APCO), National Association of State 911 Administrators (NASNA), and the National Emergency Number Association (NENA), which have independently developed robust standards for call-taking and dispatching procedures, as well as workforce training to resolve differences and adopt a set of minimum standards and certifications for use across the industry and country.

- Articulating successful minimum standards so that call answering time is not equated, in and of itself, with quality.

- Study and articulate cost-benefit analysis. Sustainable care (for an individual or a community) will be cheaper in the long run than repeated crisis interventions.

- Build resource-pooling, shared economies, and/or or cost-sharing structures for smaller communities that cannot independently support the solutions they need.

- Consider the other resources that non-police response units will need.

- Evaluate whether responders will be able to get to an emergency fast enough from wherever they are based. Strategize around location, deployable assets, and other factors.

- If ECCs are not able to meet these minimum standards, they should consider consolidating and/or sharing resources with another ECC to bring them into compliance.

- A streamlined federal accountability and oversight program, modeled after the consent decree and pattern and practice investigations led by the Department of Justice that provide opportunity for thorough investigation and collaborative and/or sanctioned reform practices that are closely and regularly monitored and assessed.

- Address the many questions around 911 revenues and associated demands for service (see Action 5, above) and offer potential remedies given that the vast majority of 911 communications are increasingly originating from mobile devices, yet user fees are largely being generated by telephone billing location, which in many instances may not be the same place as where 911 calls (or associated ECC) are initiated.

- Require ECCs to offer all advanced services to include text-to-911[3] and have the ability to receive enhanced multimedia and location data in compliance with the i3 standards[4] (particularly for people with disabilities and people for whom English is not a first language).

- As noted in Recommendation 6 (chapter eight) on data and tech, the public expectation of what services are available in our nation’s 911 centers has greatly outpaced reality. ECCs that have upgraded the infrastructure and now offer true NG911 services enjoy a more secure, redundant, flexible, and accessible system, and the time has come to standardize this experience across the nation. With cybersecurity being a top priority for communication centers and government entities, the NAS panel should advise on (a) how federal and state legislatures may pass laws and/or executive orders and (b) how to assign financial resources for all ECCs to elevate to this more secure and complete level of service.

- Develop a credentialing process for technology vendors to apply and demonstrate compliance with all industry ANSI standards. The two largest emergency communication industry associations have coordinated the creation of much-needed standards that have been vetted and certified by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI). The standards address many topics to include training, hiring, operations, and technology. Vendors often state “Meets ANSI Standards” in their marketing materials. It is recommended that the associations create a collaborative credentialing process to ensure the vendors are making true statements in regard to their standards compliance.

- Establishing national and state-level minimum standards for how ECCs operate to ensure consistent, equitable access and delivery of 911 services and related certified response options (e.g., certified language translation and standards for training in cardiopulmonary resuscitation), regardless of location in the country.

7. Incentivize transformation by creating a federal grant program to be run through the NAS panel’s to-be-determined location for federal 911 placement. This grant program should include:

- A one-time capital and data infrastructure upgrade, allowing states to keep a portion of these grants for administration, of $300 million to help enhance security and connectivity among federal, state, and local emergency management centers. These upgrades will also facilitate greater adoption and practice for ECCs to access data and follow standards.

- We recommend that funding be conditional on enacting and adhering to the standards and data linkages that will be recommended by the NAS panel.

- Up to five years in funding for operational transformation to help support personnel and related costs (see chapter five on workforce) associated with:

- Including $350 million to support recurring salary upgrade needs, inclusive of state and local matching funds. This will help significantly offset up-front costs resulting from 911 professional title reclassification.

- We recommend that localities and states meet 25% of the 75% in matching funds, that will gradually be reduced every year for the five years of this investment.

- Providing a $150 million boost for the current workforce to meet new standards through training and other measures, including:

- Implementing workforce traumatic stress reduction practices, to provide greater levels of support for this growing and hurting workforce facing unsustainable mandatory overtime, high vacancy rates, burnout, and other factors compounding the stress that results from handling 911 calls.

- Developing and implementing 911 community boards.

- Supporting the development of a complete first responder ecosystem workforce to include on-scene, virtual, and hotline professionals.

- State college tuition, loan forgiveness, and access to Pell Grants to be made available for the entire first responder ecosystem workforce—including 911 professionals, hotline professionals, and on-scene and virtual responders.

- Including $350 million to support recurring salary upgrade needs, inclusive of state and local matching funds. This will help significantly offset up-front costs resulting from 911 professional title reclassification.

8. Tie federal funding to compliance with criteria to include that states and localities receiving grants have:

- 911 state directors who meet some baseline standards to be set by the federal taskforce.

- 911 governance boards that meet criteria set by the federal taskforce and are inclusive of multiple community perspectives.

- Met interoperability, data, community, and transparency standards such as those suggested in this blueprint.

- A state 911 procurement officer with credentials established by the taskforce and NAS panel to review and approve technology upgrades, with an eye toward shared technology resources that will save money and increase redundancies in the event an ECC goes offline or is overwhelmed by call volume.

- Followed and accessed as needed federal support in procurement, which could be a meaningful lever of change allowing states and localities to enter into group bargaining and procurement that could help control costs and level the playing field for ECCs.

- Tie federal funding to compliance with criteria to include that states and localities receiving grants have

- Obligatory agreements to share call data with the public.

Federal support on research for these essential inquiries will be critical. Please see the full research agenda in chapter ten and Appendices G and H.

[1] The field benefits tremendously from estimates that NENA provides, which are some of the only data we have on 911. Yet many of the statistics they publish—e.g., that 240 million calls are made to 911 each year—have gone unchanged for years and do not offer the methodology by which the estimates have been generated. As the research agenda (described in the next chapter) articulates, it is absolutely essential that we have a national understanding of how many calls are made to 911, for what, where, how/if they are responded to, and what the associated outcomes are. While current telecom data may not answer all of these questions, it certainly can start to paint a picture.

[2] The FCC’s reports on fee collection and appropriation are a helpful data point: www.fcc.gov/general/911-fee-reports

[3] TTY, real-time-text, multimedia text (including voice, video, data)

[4] NENA’s family of NG911 standards—with i3 serving as the keystone—enables data-rich, secure, IP-based communications from the public, through 911, to every field responder. The new version will serve as the foundation of a twenty-first-century, broadband-based 911 ecosystem. From: https://www.nena.org/news/572966/NENA-Releases-New-Version-of-the-i3-Standard-for-Next-Generation-9-1-1.htm